By Thomas Frenette

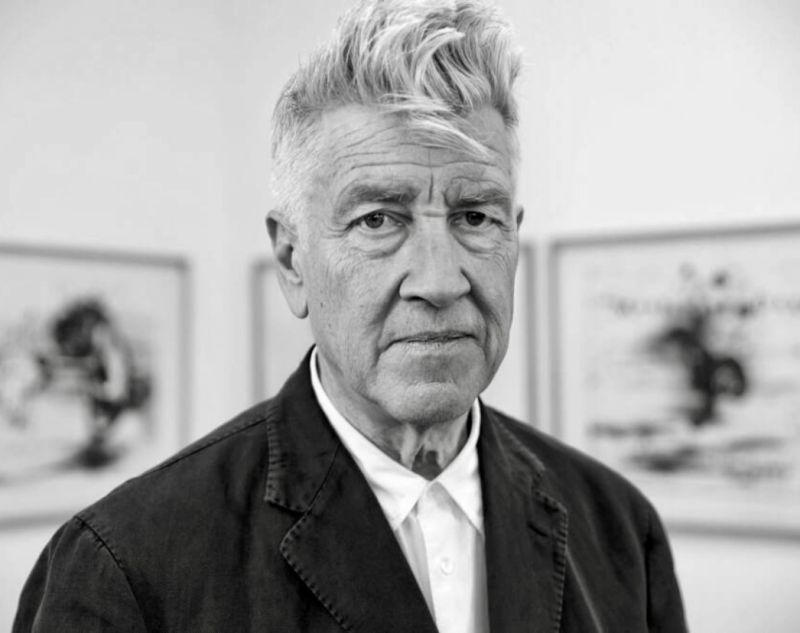

The outpouring of grief in response to David Lynch’s passing on the 15th of January, 2025, will be the very last of the shocking, off-putting, or otherwise intensely emotional public reactions he incited during his storied career. Statements from his family, friends, and collaborators have struggled to capture the essence of what David Lynch meant to them. His lifelong friend Kyle MacLachlan, star of Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet, for example, described David as someone who “was in touch with something the rest of us wish we could get to.”

In keeping with societal tendencies when landmark figures die, much of the public perceived this tragedy as if it were a close personal loss to be grieved – myself included. David Lynch was the kind of artist who could strike concurrent emotional chords in massively disparate hearts across generations through art. But what made David Lynch so unique? The answer may lie in how he articulated his ideas. In interviews, he routinely stated how unreliable words are: “as soon as you put things in words, no one ever sees the film the same way. And that’s what I hate, you know. Talking — it’s real dangerous […] it’s almost like a crime.” On the relationship between words and art, he expressed that “words are not just reductive; they are anathema to my view of art as fundamentally enigmatic.”

Given his mistrust of words, he often chose to express his ideas through sound. Both inside and outside his films, he leveraged sound to “bring people into a world and give them an experience where you can get lost in […] for years.” Over half-a-century of filmmaking, David Lynch experimented extensively with sound. For the midnight classic Eraserhead, hours of wind noises were recorded by collaborator Alan Splet in Findhorn, Scotland. These sound recordings were used throughout the film, marking the beginning of David Lynch’s use of real-world elements as points of departure into abstract soundscapes. Whereas Eraserhead’s soundtrack consists primarily of sound – except for In Heaven – later movies like Mulholland Drive feature an integrated mix of sound and song. Llorando, a Spanish arrangement of Roy Orbison’s Crying, dissolves the boundary between sound and speech. Without an instrumental accompaniment, the ‘song’ expands like a mysterious story in itself.

David Lynch was, however, involved in many art forms other than cinema; he experimented with painting, photography, furniture, music and more. He forged artistic alliances with many artists, the most enduring and significant of which was with Angelo Badalamenti. He was the composer for much of David Lynch’s work, starting with Blue Velvet, arranging the themes that defined David Lynch’s musical arsenal: twanging guitars, gentle brush drums, smoky strings, ringing organs, wailing saxophones and thick industrial sounds. While the ‘Lynchian’ aesthetic is partially defined by these instruments, the intent was also to inspire image that would accompany them. When working together, the pair would often start composing before filming because “those sounds [and] that music [ended] up conjuring the images.” Regarding the relation between sound and image, David Lynch said that “people always talk about the look of a film, they don’t talk so much about the sound of a film. But it’s equally important – sometimes more important.” This belief was the source of his mission as a filmmaker: to let sound inspire images. When David Lynch wasn’t finding inspiring images in the heartbreak ballads of singers like Roy Orbison and Chris Isaak, he worked with modern torch singers Julee Cruise and Chrystabell to create his own. In Julee Cruise’s album Floating into the Night, for example, Angelo Badalamenti composed the music, David Lynch wrote the lyrics, and Julee Cruise performed the vocals. She was most notably featured in the finale of the first season of Twin Peaks and in the film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

David Lynch, Angelo Badalamenti and Julee Cruise have passed away, but their music will live forever. Their work remains a bastion for artists to explore the indescribable mystery in our lives. For this, Kyle MacLachlan said that he will remember David Lynch as being “in tune with the universe and his own imagination on a level that seemed to be the best version of human.” David Lynch, McLachlan says, “was not interested in answers because he understood that questions are the drive that make us who we are. They are our breath.”